Myth, Magic, and Mysticism in the Age of Information by Erik Davis

Erik Davis’s TechGnosis is considered the classic text on the relation between technology and the occult. This “Afterword 2.0” was written for a new edition, just out from North Atlantic Books.

IT MAKES ME SLIGHTLY PAINED to admit it, but the most vital and imaginative period of culture that I’ve yet enjoyed unfolded in the early 1990s (with the last years of the 1980s thrown in for good measure). There was a peculiar feeling in the air those days, at least in my neck of the woods, an ambient sense of arcane possibility, cultural mutation, and delirious threat that, though it may have only reflected my youth, seemed to presage more epochal changes to come. Recalling that vibe right now reminds me of the peculiar spell that fell across me and my crew during the brief reign of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, which began broadcasting on ABC in the spring of 1990. Today, in our era of torrents, YouTube, and Tivo, it is difficult to recall the hold that network television once had on the cultural conversation, let alone the concrete sense of historical time. Lynch’s darkside soap opera temporarily undermined that simulacra of psychological and social stability. Plunging down Lynch’s ominous apple-pie rabbit hole every week, we caught astral glimmers of the surreal disruptions on the horizon ahead. I was already working as a culture critic for the Village Voice, covering music, technology, and TV, and later that year I wrote an article in which I claimed that, in addition to dissolving the concentrated power of mass media outlets like ABC, the onrushing proliferation of digital content channels and interactive media was going to savage “consensus reality” as well. It wasn’t just the technology that was going to change; the mass mind itself was, in an au courant bit of jargon from Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus, going molecular.

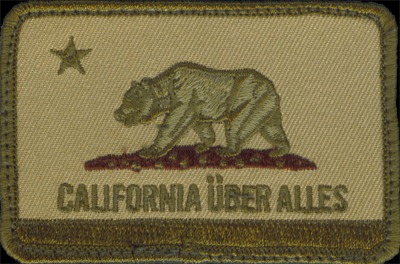

Molecular meant a thousand subcultures. Pockets of alternative practices across the spectrum crackled with millennialist intensity in the early nineties, as if achieving a kind of escape velocity. Underground currents of electronic music, psychedelia, rap, ufology, cyberculture, paganism, industrial postpunk, performance art, conspiracy theory, fringe science, mock religion, and other more or less conscious reality hacks invaded the spaces of novelty and possibility that emerged in the cracks of the changing media. Hip-hop transformed the cut-up into a general metaphor for the mixing and splicing of cultural “memes” — a concept first floated by Richard Dawkins in 1989. Postmodernism slipped into newsprint, Burning Man moved to the desert, and raves jumped the pond, intensifying the subliminal futurism of American electronic dance music into a sci-fi hedonism that turned the DJ into a nerdy shaman and the nervous system into a launching pad. The ambient music designed to fill chill-out tents helped stage a return of a pop-tech mysticism, intensified by MDMA’s glowing body-without-organs and the return to serious psychedelia aided and abetted by Terence McKenna and other Internet-enabled psychonauts. The eighties zine scene continued to flourish, but new production tools allowed publications like Mondo 2000, Magical Blend, Gnosis, and the “neurozine” Boing Boing to catapult from the DIY zone onto the magazine racks. At the same time — and with enormous effect on the weirdness to come — the zine ecology began colonizing the online hinterlands of BBSes, Usenet alt groups, and the Well (which was, well, a big BBS). Even cable access TV was getting pretty strange (at least in Brooklyn). Some wags joked that Hendrix had rightly prophesied, and that the sixties had turned out to be the nineties after all. And while that fantasy radically distorted the street politics of the former and the technology-primed economics of the latter, it did announce that the old hippie divide between a computerized technocracy and an earthy analog underground had not only broken down but dissolved.

This was, quite simply, an awesome time to be a cultural critic. At the Village Voice, then a feisty paragon of identity politics and primo alternative journalism, I was encouraged by a handful of highly skilled (and highly tolerant) editors to write about everything from cosmic heavy metal to posthumanist philosophy to The X-Files to the Zippies. Following the steps of my Voice pal and fellow tech journalist Julian Dibbell, I got a Panix dial-up account in 1993, and dove into the weirdness of alt groups, French theory listservs, and the social experiments of LambdaMOO, where I encountered a crew of highly intelligent and creative anarchist pagans that blew my mind. Those years were, by far, the most fun I ever had online. But the real initiation into the stream of technomagic that inspired TechGnosis occurred a couple years earlier, when I flew from New York to the Bay Area in order to attend the first and only Cyberthon, a paisley-flaked technology gathering whose speakers included Timothy Leary, Terence McKenna, and Bruce Sterling. Virtual reality, now making a belated comeback through Oculus Rift and related gamer gear, was all the rage. I strapped on dread-headed Jaron Lanier’s data-glove rig, and I toured the VR lab at NASA Ames with the deeply entertaining John Perry Barlow. I met a sardonic William Gibson, who single-handedly engineered our “collective hallucination” of cyberspace, and a standoffish Stewart Brand, whose Whole Earth tool fetishism presaged the Cyberthon’s meet-up of counterculture and cyberculture. For me, born in the Bay Area but raised and living on the East Coast, the Cyberthon was a strange kind of homecoming: one that only strapped me onto a new line of flight, a cruise that rode the growing updrafts of what would become the mass digital bloom.

TechGnosis was in many ways woven from the travel diary of that cruise. As a journalist, as well as a heady seeker of sorts, I was already devoted to tracking the juxtaposition of spirituality and the material grit of popular culture, a juxtaposition that in the nineties came to include new technologies, human augmentation tech, and the dawning “space” of digital mediation. Once I tuned into this techgnostic frequency, I realized that the waves radiated backward as well as forward, not just toward Teilhard’s apocalyptic Omega Point or McKenna’s jungle Eschaton, but toward the earliest technical stirrings of Paleolithic Homo sapiens. I became seized by the McLuhanesque conviction that the history of religion was really just a part of the history of media. As a pagan dabbler, I grokked that the hermetic and magical fabulations that had gone underground in the modern West had returned, like Freud’s repressed hankerings, in technological forms both built and imagined, demonic and transcendent, sublime and ridiculous. I began to track these secret histories, and my notes grew until they demanded to be a book.

Today there is so much wonderful and intelligent material on occult spirituality — in scholarship, literature, and the arts — that it is hard to remember just how esoteric this stuff was in the nineties. Peers at the time suggested that, outside certain recondite circles, my research might prove bootless given the more pressing issues — and pragmatic opportunities — associated with the digital revolution. And yet, as the pieces fell into place, as I befriended technopagans or stumbled across cyborg passages in hermetic texts, I felt I no longer had choice in the matter. I was possessed by what Teilhard had called the “demon (or angel) of Research,” which is one way of describing what takes place when the object of study turns around and grabs you by the balls. I had to write TechGnosis. And though other writers and historians were tuned into these questions both before and alongside me, I am chuffed, as the British say, that scholars, hackers, mystics, and artists alike continue to draw from the particular Wunderkammer I assembled.

I think TechGnosis continues to speak despite its sometime anachronism because it taps the enigmatic currents of fantasy, hope, and fear that continue to charge our tools, and that speak even more deeply to the profound and peculiar ways those tools shape us in return. These mythic currents are as real as desire, as real as dream; nor do they simply dissipate when we recognize their sway. Nonetheless, technoscience continues to propagate the Enlightenment myth of a rational and calculated life without myths, and to promote values like efficiency, productivity, entrepreneurial self-interest, and the absolute adherence to reductionist explanations for all phenomena. All these day-lit values undergird the global secularism that forms the unspoken framework for public and professional discourse, for the “worldview” of our faltering West. At the same time, however, media and technology unleash a phantasmagoric nightscape of identity crises, alternate realities, memetic infection, dread, lust, and the specter of invisible (if not diabolical) agents of surveillance and control. That these two worlds of day and night are actually one matrix remains our central mystery: a rational world of paradoxically deep weirdness where, as in some dying earth genre scenario, technology and mystery lie side-by-side, not so much as explanations of the world but as experiences of the world.

Take the incipient Internet of things — the invasion of cheap sensors, chips, and wirelessly chattering mobile media into the objects in our everyday world. The nineties vision of “cyberspace” that partly inspired TechGnosissuggested that a surreal digital otherworld lay on the far side of the looking glass screen from the meatspace we physically inhabit. But that topology is being decisively eroded by the distribution of algorithms, sensing, and communicating capabilities through addressable objects, material things that in some cases are growing extraordinarily autonomous. There are sound reasons for these developments, which arguably will greatly increase the efficiency and power of individuals and organizations to monitor, regulate, and respond to a world spinning out of control. As such, the Internet of things offers consumers another Gernsback carrot, another vision of a future world where desire is instantly and transparently satisfied, where labor is offloaded onto servitors, and where we are all safely watched over by machines of love and grace. But if the social history of technology provides any insight at all — and I would not have written TechGnosis if it didn’t — this fantasy is necessarily coupled to its own shadow side. As in the tale of the sorcerer’s apprentice, algorithmic agents will be understood as possessing a mind of their own, or serve as proxies for invisible agents of crime or all-watching control. Phil Dick’s prophecy, cited earlier in TechGnosis, is here: our engineered world is “beginning to possess what the primitive sees in his environment: animation.” In other words, a kind of anxious animism, the mindframe once (wrongly) associated with the primitive origins of religion, is returning in a digitally remastered form. Intelligent objects, drones, robots, and deeply interactive devices are multiplying the nonhuman agents with whom we will be forced to negotiate, anticipate, and dodge in order to live our lives. Sometimes remote humans will be at the helm of these artifacts, though we may not always know whether or not people are directly in the loop. But all of it — the now wireless world itself — will become data for the taking. So if Snowden’s NSA revelations felt like the cold shadows of some high-flying nazgûl falling across your backyard garden, get ready to be swallowed up in the depths of the uncanny valley.

One side of this new animism we already know by another name: paranoia, which will continue to remain an attractive (and arguably rational) existential option in our networked and increasingly manipulated world. Even if you set aside the all-too-real problems of political and corporate conspiracy, the root conditions of our hypermediated existence breed “conspiracy theory.” We live in an incredibly complicated world of reverberating feedback loops, one that is increasingly massaged by invisible algorithmic controls, behavioral economics, massive corporate and government surveillance, superwealthy agendas, and insights from half a century of mind-control ops. It is impossible to know all the details and agendas of these invisible agents, so if we try to map their operations beyond the managed surface of common sense and “business-as-usual,” then we almost inevitably need to tap the imagination, with its shifty associative logic, as we build our maps and models out of such fragmentary knowledge. That’s why the intertwingled complexities — aided and abetted by the myopic and self-reinforcing conditions of the Internet — found even in the most concrete conspiracy investigations inevitably drift, as systems of discourse, towards more arcane possibilities. The networks of influence and control we construct are fabulated along a spectrum of possibility whose more extreme and dreamlike ends are effectively indistinguishable from the religious or occult imagination. JFK = UFO. Analyses of the “twilight language” hidden in the latest school shooting, or Illuminati hand signs in hip-hop videos, or the evidence for false flag operations buried in the nitty-gritty data glitches of major news events — all these disturbing and popular practices suggest an allegorical art of interpretation that is impossible to extricate from our new baroque reality, with all its reverberating folds of surface and depth. Paranoia’s networks of hidden cause not only resonate with the electronic networks that increasingly complicate and characterize our world, but suggest the ultimate Discordian twist in the plot: that the greatest forms of control are the stories we tell ourselves about control.

Indeed, the most obvious place to track the prints of myth, magic, and mysticism through contemporary technoculture is, of course, in our fictions. At the beginning of the nineties, geek culture was largely a nerdy niche, its genres and fannish behaviors leagues away from serious cool. But as geeks gained status in the emerging digital economy, the revenge of the nerds was on. The battle is now over, and the nerds rule: popular culture is dominated by superheroes, science fiction, sword and sorcery, RPGs, fanfic, Comicons, Lovecraftmania, cosplay. Geek fandoms have gone thoroughly mainstream, propagated through gaming, Hollywood, online newsfeeds, massive advertising campaigns, and office cubicle decor. With a qualified exception for hard SF, these genres and practices are all interwoven, sometimes ironically, with the sort of occult or otherworldly enchantments tracked in TechGnosis. But its not just geek tastes that rule — it’s geek style. As the software analytics company New Relic put it in a recent ad campaign, we are all “data nerds” now. In other words, we like to nerd out on culture that we increasingly experience as data to play with. The in-jokes, scuttlebutt, mash-ups, and lore-obsession of geekery allow us, therefore, to snuggle up to the uncanny possibilities of magic, superpowers, and cosmic evil without ever losing the cover story that makes these pleasures possible for modern folks: that our entertainments are “just fictions,” diversions with no ontological or real psychological upshot, just moves in a game.

The funny thing about games and fictions is that they have a weird way of bleeding into reality. Whatever else it is, the world that humans experience is animated with narratives, rituals, and roles that organize psychological experience, social relations, and our imaginative grasp of the material cosmos. The world, then, is in many ways a webwork of fictions, or, better yet, of stories. The contemporary urge to “gamify” our social and technological interactions is, in this sense, simply an extension of the existing games of subculture, of folklore, even of belief. This is the secret truth of the history of religions: not that religions are “nothing more” than fictions, crafted out of sociobiological need or wielded by evil priests to control ignorant populations, but that human reality possesses an inherently fictional or fantastic dimension whose “game engine” can — and will — be organized along variously visionary, banal, and sinister lines. Part of our obsession with counterfactual genres like sci-fi or fantasy is not that they offer escape from reality — most of these genres are glum or dystopian a lot of the time anyway — but because, in reflecting the “as if” character of the world, they are actually realer than they appear. That’s why we have seen the emergence of what scholars call “postmodern religion” between the cracks of our fandoms: emotionally wrenching funerals on World of Warcraft, Mormon (and Scientological) science fictions, Jedi Zen, even Flying Spaghetti Monster parodies that find themselves wrestling with legal definitions of “real” religion.

But it is may be in horror that we most clearly see the traces of technological enchantment today, a trace as easy to track as the eerie frame of Slender Man. Emerging from the mines of creepypasta, a hard-geek zone of Internet-enabled horror tales designed to propagate virally, Slender Man first appeared as a faceless and abnormally tall spook in a black suit lurking in the background of an otherwise placid playground scene posted to the comedy prankster site Something Awful. Memetically, Slender Man had the goods, and soon found himself multiplied through a vast number of images, videos, cosplay costumes, and online narratives. I like to think Slender Man’s popularity may have had something to do with his resemblance to the lanky and reserved H. P. Lovecraft — a resonance underscored by the tentacles he sometimes sports. Lovecraft’s so-called Cthulhu mythos is the paragon of that weird interzone aimed at by so many horror franchises, which seek to achieve an “as if” reality through self-referential and intertextual play that seems to bring the phantasm further into being. This play, it could be argued, is almost what the Internet is designed for. But here we speak not of fell Cthulhu, nor of the dreaded Necronomicon and its various incarnations in print. Instead, it was the gangly Slender Man who stepped from cyberspace into the real when two twelve-year-old girls from Wisconsin — perhaps not unlike the adolescents in the original Photoshopped playground image — stabbed a classmate in the woods in order to please the crowd-sourced wraith. The possible mental instability of the girls is not really the point here — it is the rapid Net-enabled mediation of fictions into something more like folklore, but a folklore now rendered viral and invasive through the virtual and social media that increasingly circulate and condition “consensus reality.” Less horrifying examples of this sort of phantasmic logic can also be found in the fringe phenomena of Otherkin and tulpamancy — Internet-fueled subcultures that proclaim the ontological reality of beings and identities cobbled together in part from fandom and modern folklore, but gaining their consistency through the digital mediation and collective construction of unusual psychological experience.

In a recent essay for the book Excommunication, Eugene Thacker examines the constitutive role that media have played in many supernatural horror tales. In normal life, the different times and places that communication technologies tie together belong to the same plane of reality — New Caledonia may be an exotic place, but when I FaceTime someone there, I am still communicating with a locus in Terran spacetime. But in supernatural horror, media create portals between different orders of reality, what Bruno Latour would call different ontological “modes.” Examples include the cursed videotape in the J-horror classic Ringu, or the device in Lovecraft’s “From Beyond” that reveals the normally invisible beasties that flit about our dimension. The paradox of such fictions is that the remoteness of the otherworld is made immanent in the technology itself, present to hand in an actual artifact that still oozes otherness. The device it grows haunted, or weird, not because the technology breaks down, but because it works too well. Glitches, noise, and stray signals are no longer technical faults but the flip side of another order of being leaking through. Though Thacker is interested in horror fiction, a similar bleed between ontological realms occurs in some paranormal practices. Take the legions of photographers drawn to angels, ghosts, and manifestations of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Though the ubiquity of phones and post-processing techniques should, according to the rationalist rules of evidence, diminish the believability of specters or heavenly beings, some photographers have developed a rich iconography of lens flares, floating orbs, streakers, and other mysterious marks that indicate otherness. Media will always present technical anomalies, and such anomalies will always offer stages for oracular and otherworldly perception, whether or not you consider such perceptions as internally-generated apophenic projections, or as living traces of those mysterious orders of presences that seem to ghost communication.

The spaces of novelty that TechGnosis explored were largely opened up by developments in technical media, including the digital revolution that emerged at the end of the twentieth century. But a far more fundamental example of Thacker’s “weird media” remains the human sensorium itself: at once the realtime flux of perception, feeling, and cognition, as well as the neural substrate that conditions, and arguably causes, this ongoing mediation of reality. And it is the human sensorium, conscious and unconscious, that has become the ultimate object of technical manipulation, augmentation, and control. In part, this represents the steady march of technoscience and the rational Enlightenment project it represents, and as such would seem to suggest that we are close to banishing all those hoary ghosts of yore. But there is a funny paradox about the neuroscientific bid to map the workings of the mind: the more totalizing the effort to explain consciousness and all its features, the more seriously researchers must engage, in a non-trivial manner, the most marvelous and otherworldly events: lucid dreams, placebo healings, out-of-body journeys, near-death experiences, extreme-sports highs, meditative insights, DMT otherworlds, and a whole host of apparitions, premonitions, and other paranormal phenomena. While intricate (and intransigent) sociobiological explanations for all this weirdness will continue to be presented as the only serious game in town, and while the organized (and well-funded) armies of militant skeptics will continue to fan the smokescreen that surrounds serious parapsychological research, the phenomena themselves must be taken seriously as experiential realities. Weirdness, in other words, cannot simply by swept under the rationalist carpet — it is thoroughly woven into the world that needs to be explained — and that will continue to be experienced, above and beyond all explanation.

In “The Spiritual Cyborg,” for my money the most important chapter in this book, I talked about how the extreme view of human being presented by reductionist science — that we are basically neo-Darwinian DNA robots — has itself been hijacked by some techgnostics for the purposes of mystic liberation and visionary reality programming. This unexpected twist, by which skepticism becomes a tool of spirit, is one of the key points of the anthropological perspective I favor. It is not that religious visions or spiritual values or occult cosmologies are special, unvarnished forms of truth. They are indeed stories and constructions, fabulations and fabrications we use (and mis-use) to get by. The point instead is that the demands of cold hard reality — whether those are framed as reductive naturalism, economic pragmatism, or a harsh and arrogant skepticism that does injustice to all manner of realities hard and soft — are also stories and constructions. Facts are very special objects, which is why they must be constructed through such careful and painstaking methods. But they are still human fabrications, especially when we noise them abroad through popular media or glue them together into more or less impervious worldviews. We are all wearing tool belts here, scientists and mystics alike, fashioning experience into artifacts and realities that feedback on us, inevitably, as stories, shaping us in turn. Backed up by sociobiology or neuroscience — or the pop-science simulacra of sociobiology and neuroscience — many of today’s dominant technological stories are devoted to augmenting the competitive advantage of the same old rational agent, or, more insidiously, to manipulating subjectivity for purposes of economic or social control. Instead, I hope that we rapidly and creatively expand our range of what the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk calls “anthropotechnics” — those processes and practices that turn us into perceiving subjects, that train our capacities, that bootstrap our own transformation. Rational calculation should never tame what Sloterdijk describes as the “vertical tension” that pulls us ever upward and outward, and toward the acrobatics of the spirit.

I admit that sometimes this seems like a thin hope indeed. A massage therapist I know up in Northern California recently remarked that, faced with the apparent gloaming of human history, most folks she knew were either rooting themselves in more embodied, local, and offline lives, or were diving with more mutant gusto into the intertwingled webwork of the digital cosmopolis. I have always been a fan of the “middle way” — between reason and mystery, skepticism and sympathy, cool observation and participation mystique. Facing the technological future, I remain a being of ambivalence, suspended, like many, I suspect, in a vexed limbo of bafflement, wonder, denial and despair. I remain fascinated and amazed by our realtime science fiction and the cognitive enhancements (and estrangements) provided by our increasingly posthuman existence. But I also find myself profoundly alienated by the culture of consumer technology, aggravated by the fatuous and self-serving rhetoric of Silicon Valley tools, horrified by our corporatized surveillance state, and saddened by the steely self-promoting brands that so many people, aided and abetted by social media, have become. I was born in the Summer of Love, and while my generation had the uncanny privilege of witnessing the dawn of mass digital culture, I increasingly find myself communing with the other side of the coin: the analog sunset it has also been our blessing to witness and undergo. Like the warm crackles of vinyl, or the cosmic squiggles of a wild modular synth, or the evocative glow of an actual Polaroid, the resonant frequencies of a less networked world still illuminate all my relations. I do not feast on nostalgia, but nostalgia is not the same thing as affirming the gone world that still signals us now, in the timeless time of transmission.