Were JG Ballard's billboards actually coded Salvador Dalí paintings?

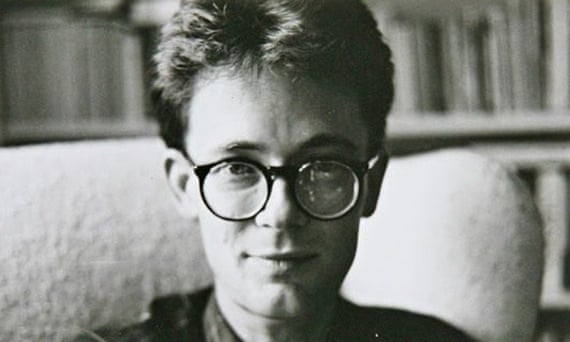

JG Ballard was best known for his pioneering dystopian fiction, and his twisted reimaginings of the technological landscape. The Atrocity Exhibition (1970) – which tells of a man’s descent into psychosis amid the bustling, consumer world – was banned in the US, while Crash, published three years later, saw one critic proclaim Ballard as “beyond psychiatric help” (a diagnosis he often boasted about during interviews).

But more than a decade earlier, in 1958, Ballard created a series of unusual and mystifying commercial billboards, which he called Project for a New Novel. With their motley amalgam of seemingly unrelated scientific journal excerpts, perplexing words, names and phrases, they supposedly held some underlying narrative. But what exactly was it? The puzzle has mystified Ballardian scholars and enthusiasts for decades.

But we may finally have the answer: these billboards were encrypted replicas of Salvador Dalí paintings.

Ballard imagined these billboards spread across London, as a cryptographic narrative that would stand alongside the most powerful brands in the world. He was fascinated by the power of the consumer landscape on the unconscious mind, and how advertising was able to channel and manipulate society on a mass scale. While most billboard ads focus on quickfire bursts of information, eye-catching imagery and memorable phrases, Ballard inverted this process: stripping them of image in favour of text, and making the message wilfully inscrutable. In doing this he urged the viewer, the consumer, to formulate their own subjective narrative through these fragmentary collages, thus empowering the consumer and reinvigorating the imagination.

Ballard’s hankering for psychic stimulation was shared by the surrealist artists, who were among his biggest artistic influences. Most important of them all to him was Dalí whom the author hailed in a 2007 Guardian article as “the greatest painter of the 20th century”.

Returning to Ballard’s billboards in the context of his love of Dalí, a picture begins to emerge that links the esoteric words, names and phrases with soon-to-be-published stories. ( a subire...)