Yves Charles Zarka : Le populisme et la démocratie des humeurs

@ Cités, n.49, 2012

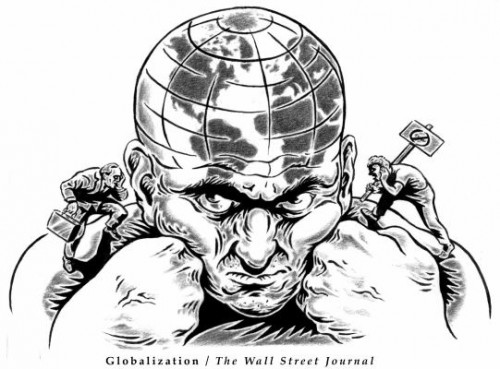

Le retour du populisme en France, dans la plupart des pays européens et ailleurs ne peut être simplement expliqué comme le résultat de la stratégie de certains partis politiques extrêmes qui font de la démagogie leur fonds de commerce en jouant sur les peurs des populations, voire en les créant. Bien entendu, ces partis existent – pas seulement à l’extrême droite – et ils font en effet profession de populisme, c’est-à-dire suscitent et activent les passions les plus négatives, et même les plus perverses pour étendre leur audience et entretenir leurs troupes : construction de boucs émissaires (les immigrés, les élites), promesses d’autant plus exorbitantes que les moyens élaborés pour les satisfaire sont indigents, désignation permanente de l’ennemi à attaquer ou à détruire pour que la justice, la prospérité et le bonheur soient restaurés. S’en tenir à une telle explication serait, je crois, passer à côté de ce qui fait la spécificité du moment présent. Le retour du populisme et son extension ne sont pas la réactivation d’une essence transhistorique de la manipulation des peuples.

2Ce qui caractérise le populisme aujourd’hui, c’est qu’il se développe dans les sociétés démocratiques dont les populations sont en général dotées d’un haut niveau d’éducation et ne se laissent pas manipuler facilement parce qu’elles comprennent les stratégies politiques des uns et des autres. Sa cause est plus profonde : elle concerne un aspect de la dégradation de la démocratie aujourd’hui, c’est pourquoi le populisme n’est pas le fait d’un seul parti mais de la plupart. Il est difficile d’y résister, et pourtant il faut absolument lui résister. Pour le dire d’une phrase : le populisme devient en effet un mode dominant du rapport aux citoyens dans des démocraties qui ont perdu le sens de la délibération publique, de la consultation populaire et du bien commun.

3En effet, l’exercice du pouvoir politique est aujourd’hui scindé en deux dimensions très différentes l’une de l’autre. La première consiste en une technicisation politique biaisée. En ce sens, celle-ci est un mixte d’expertises plus ou moins objectives et d’intérêts plus ou moins inavouables. Les expertises, pour lesquelles sont rémunérés des économistes ou des financiers, sont censées exposer la seule solution possible dans un domaine et une situation particulière : par exemple la solution pour sortir de la crise financière actuelle. Mais précisément pour que la solution puisse être présentée comme la seule possible, il ne faut pas la nommer « crise financière », mais « crise de la dette ». Par ce biais, on fait comme si la dette était un phénomène à expliquer pour lui-même, comme si la cause de la dette était à elle seule la cause de la crise. Réponse dans ce contexte : certains États ont trop dépensé, ils se sont endettés au-delà de toute mesure. D’où la seule et unique solution possible : il faut mettre en place une politique de rigueur pour réduire l’endettement et un dispositif de sanctions contre les États qui ne s’y soumettraient pas ou qui ne respecteraient pas les engagements pris. On écarte de cette façon un bon nombre d’autres solutions possibles, comme le changement de statut de la BCE (Banque Centrale Européenne), le contrôle des banques, la taxation des transactions financières, la remise en cause radicale et même la traduction devant un tribunal international des agences de notation qui ont, dans bien des cas, comme celui des produits Subprimes (notés AAA jusqu’à la catastrophe de 2008), sciemment trompé à la fois des populations entières et même des États, etc. Ces solutions alternatives, dont le sérieux est accrédité par un bon nombre des meilleurs économistes, ne sont même pas évoquées. Seule est retenue la prétendue seule solution possible, comme le faisait l’actuel Chef de l’État, Nicolas Sarkozy, dans son interview au journal Le Monde (13/12/2011) à propos de l’accord européen de Bruxelles censé nous faire sortir de la crise. Ce qui est présenté dans ce cas comme la seule solution possible pour la sortie de la crise est une vérité tout autre chose que cela : le résultat d’une vision partielle et partiale, biaisée donc, en fonction d’autres motivations qui relève d’intérêts. Quels sont ces intérêts ? Il varient suivant les cas, mais il est clair qu’il sont opposés au intérêts des différents peuples européens, puisque en somme on fait payer aux populations par la rigueur et l’impôt des dettes dites souveraines (mais qu’il faudrait dire de servitude) des États dont elles ne sont nullement responsables. Ce sont souvent ceux-là mêmes (Nicolas Sarkozy en particulier par ses cadeaux fiscaux invraisemblables entre autres choses) qui ont creusé la dette, qui se donnent désormais pour les meilleurs médecins connaisseurs de l’unique traitement possible. On voit comment l’intérêt inavoué ou inavouable (il ne faut pas faire peser la charge sur la frange la plus favorisée de la population, il ne faut pas que la responsabilité des gouvernants apparaisse, etc.) pèse sur la conception de la prétendue unique solution possible.

4Ce que j’ai appelé ci-dessus, la technicisation politique biaisée est le nerf des pratiques de pouvoir aujourd’hui. Elle ne concerne pas uniquement la France, mais l’ensemble des États européens et même au-delà. Ce que l’on appelle gouvernance, n’est en réalité rien d’autre que l’art de faire passer pour des solutions techniques salvatrices des intérêts de classe. Quand la démarche réussit, c’est-à-dire lorsque l’illusion a pris, on appelle cela « bonne gouvernance ». De ce point de vue, toute délibération publique sur les options, les finalités et les choix a disparu. Elle apparaîtrait même comme dangereuse, parce que susceptible de rejeter « la seule solution possible ». Pour poursuivre toujours sur l’exemple de la technicisation biaisée en quoi consiste l’accord européen mis en place par Angela Merkel et Nicolas Sarkozy : il allait de soi que les peuples européens ne seraient pas consultés pour valider l’accord. La technicisation biaisée du pouvoir démocratique a peur du peuple. Si Angela Merkel et Nicolas Sarkozy sont incontestablement élus démocratiquement, en revanche leur exercice du pouvoir n’a plus rien de démocratique. C’est là que l’on passe à la post-démocratie.

5Cependant, pour que ce qui n’est plus une pratique démocratique du pouvoir puisse passer encore pour de la démocratie, il faut faire intervenir la seconde dimension de l’exercice du pouvoir. Cette seconde dimension consiste en une excitation des humeurs des populations : en particulier par la peur. Cette passion est à la fois sollicitée et apaisée, au moins en apparence, par des réactions immédiates de tel ou tel Ministre, réactions susceptibles de calmer la peur et de faire renaître l’espoir à un moment donné sans se soucier nullement des conséquences à plus long terme, ni même de savoir si là encore le remède prétendu à la peur n’est pas pire que le mal. C’est ce rapport aux humeurs du peuple qui commande aujourd’hui le rapport du pouvoir aux citoyens en donnant l’apparence du souci dans lequel le pouvoir tiens le peuple. Le populisme, dans sa forme actuelle, n’est rien d’autre que cette politique qui compense la technicisation biaisée du pouvoir par une prise sur les humeurs du peuple. La démocratie s’est ainsi dégradée en gouvernance post-démocratique, d’un côté, et populisme de l’autre. La démocratie dégradée dont je parlais au début consiste dans cette démocratie des humeurs populaires qui commande les politiques de sécurité, de justice, de santé et d’éducation etc. Mais les humeurs des peuples sont changeantes, il est le plus souvent illusoire de penser qu’on les maîtrise. C’est pourquoi les populistes sont des apprentis sorciers qui peuvent conduire, toujours pour satisfaire les humeurs, à des pratiques ou à des législations tout à fait irrationnelles et dangereuses, l’histoire nous en donne de nombreux exemples.

6La délibération démocratique est un rapport légitime au peuple qui suppose non seulement de ne pas solliciter ou répondre aux humeurs passagères des citoyens, mais en outre de leur résister. La démocratie suppose le temps, le privilège de la raison, la capacité à déterminer le bien commun au delà de la prochaine échéance électorale. Mais cela la démocratie dégradée en technicisation biaisée du pouvoir, d’une part, et sollicitation des humeurs du peuple, d’autre part, en est incapable. On voit donc comment le populisme des humeurs peut se loger dans tous les partis politiques. Est-ce que le Front national est plus populiste que l’UMP aujourd’hui ? Ce n’est pas sûr. Est-ce que le Front de gauche est plus populiste que le Parti socialiste aujourd’hui ? Peut-être, mais ce n’est pas sûr. En tout état de cause le populisme s’infiltre dans tous les partis. Il faut savoir y résister, il faut savoir ne pas céder à cette pathologie de la démocratie. Lorsque l’exercice du pouvoir maintient les citoyens systématiquement hors de la consultation et de la délibération sur les choix collectifs, sous prétexte que les peuples ne savent pas, ou ne croient pas ce qu’ils savent, ou encore ne veulent pas ce qui est bon pour eux, alors on infantilise le peuple et on fait le lit des populistes de tout acabit et de toute couleur politique.

Yves Charles Zarka: Professeur à la Sorbonne, université Paris Descartes, chaire de philosophie politique, il est notamment l’auteur de La Décision métaphysique de Hobbes. Conditions de la politique (Vrin, 1987, 2e édition, 1999) ; Hobbes et la pensée politique moderne (PUF, 1995 ; 2e édition, 2001) ; Philosophie et politique à l’âge classique(PUF, 1998) ; La questione del fondamento nelle dottrine moderne del diritto naturale (Naples, Editoriale Scientifica, 2000) ; L’Autre Voie de la subjectivité (Beauchesne, 2000) ; Figures du pouvoir. Études de philosophie politique de Machiavel à Foucault (PUF, 2001 ; 3e édition, 2001) ; Quel avenir pour Israël ? (en collab. avec Shlomo Ben Ami et al., PUF, 2001, 2e édition en poche, coll. « Pluriel », 2002) ; Hobbes the Amsterdam Debate (Débat avec Q. Skinner), (Hildesheim, Olms, 2001) ; Difficile tolérance (PUF, 2004) ; Un détail nazi dans la pensée de Carl Schmitt (PUF, 2005) ;Réflexions intempestives de philosophie et de politique (PUF, 2006) ; Critique des nouvelles servitudes (PUF, 2007) ; La Destitution des intellectuels (PUF, 2010).

Il a également publié Raison et déraison d’État (PUF, 1994) ; Jean Bodin : nature, histoire, droit et politique(PUF, 1996) ; Aspects de la pensée médiévale dans la philosophie politique moderne (PUF, 1999) ; Comment écrire l’histoire de la philosophie ? (PUF, 2001) ; Machiavel, Le Prince ou le Nouvel Art politique (PUF, 2001) ; Penser la souveraineté (2 vol.) (Pise-Paris, Vrin, 2002) ; Les Fondements philosophiques de la tolérance (3 vol.) (PUF, 2002) ; Faut-il réviser la loi de 1905 ? (PUF, 2005) ; Les Philosophes et la question de Dieu (en collab. avec Luc Langlois, PUF, 2006) ; Matérialistes français du XVIIIe siècle (en collab., Paris, PUF, 2006) ; Hegel et le droit naturel moderne (en collab. avec Jean-Louis Vieillard-Baron) (Vrin, 2006) ; Monarchie et République au XVIIe siècle (PUF, 2007) ; Kant cosmopolitique (L’Éclat, 2008) ; Carl Schmitt ou le Mythe du politique (PUF, 2009), Repenser la démocratie (Paris, Armand Colin, 2010).

Il a également publié Raison et déraison d’État (PUF, 1994) ; Jean Bodin : nature, histoire, droit et politique(PUF, 1996) ; Aspects de la pensée médiévale dans la philosophie politique moderne (PUF, 1999) ; Comment écrire l’histoire de la philosophie ? (PUF, 2001) ; Machiavel, Le Prince ou le Nouvel Art politique (PUF, 2001) ; Penser la souveraineté (2 vol.) (Pise-Paris, Vrin, 2002) ; Les Fondements philosophiques de la tolérance (3 vol.) (PUF, 2002) ; Faut-il réviser la loi de 1905 ? (PUF, 2005) ; Les Philosophes et la question de Dieu (en collab. avec Luc Langlois, PUF, 2006) ; Matérialistes français du XVIIIe siècle (en collab., Paris, PUF, 2006) ; Hegel et le droit naturel moderne (en collab. avec Jean-Louis Vieillard-Baron) (Vrin, 2006) ; Monarchie et République au XVIIe siècle (PUF, 2007) ; Kant cosmopolitique (L’Éclat, 2008) ; Carl Schmitt ou le Mythe du politique (PUF, 2009), Repenser la démocratie (Paris, Armand Colin, 2010).

.jpg)