Intervista di Simon Choat su "Masse, potere e postdemocrazia nel XXI secolo" a cura dei blog Obsolete Capitalism e Rizomatika. Intervista raccolta il 16 giugno 2013

EDIT: E' disponibile e scaricabile online/free download QUI il libro "Nascita del populismo digitale. Masse, potere e postdemocrazia nel XXI secolo" che raccoglie tutte le interviste di Choat, Parikka, Sampson, Newman, Berti, Toscano, Parisi, Terranova e Godani. Abbiamo raccolto l'intervista di Choat in questo PDF.

Masse, potere e postdemocrazia nel XXI secolo

'Fascismo di banda, di gang, di setta, di famiglia, di villaggio, di quartiere, d’automobile, un Fascismo che non risparmia nessuno. Soltanto il micro-Fascismo può fornire una risposta alla domanda globale: “Perchè il desiderio desidera la propria repressione? Come può desiderare la propria repressione?'

—Gilles Deleuze, Fèlix Guattari, Mille Piani, pg. 271

Parlare di 'micro-fascismo' per di più è utile nella misura in cui richiama la nostra attenzione alle pratiche sociali quotidiane e agli investimenti affettivi che rafforzano i centri di potere: il fascismo può svilupparsi, almeno in parte, per il desiderio o di un senso d'ordine o di partecipazione, per sentirsi parte di qualcosa, un desiderio che può diventare particolarmente forte in tempi di crisi e che può manifestarsi in modi autoritari. Questo è il motivo per cui dobbiamo essere particolarmente diffidenti nei confronti del 'populismo digitale' di una forza come il "grillismo": il suo appello al desiderio delle persone di sentirsi parte di un 'movimento' è rafforzato dal potere d'attrazione narcisistico dei social media.

Infine, una spiegazione approfondita dell'attuale ascesa degli autoritarismi richiederebbe un'analisi storica, concreta, di lungo periodo, che comprenda, non solo l'attuale crisi economica, ma anche una serie di altri fattori tra i quali va incluso - ma non limitato a - l'ascesa del neoliberismo negli ultimi trent’anni, l'aumento della disoccupazione, il depotenziamento e declino dei sindacati e della sinistra socialdemocratica.

Sul micro-fascismo

OC Partiamo dall’analisi di Wu Ming, esposta nel breve saggio per la London Review of Books intitolato 'Yet another right-wing cult coming from Italy', che legge il M5S e il fenomeno Grillo come un nuovo movimento autoritario di destra. Come è possibile che il desiderio di cambiamento di buona parte del corpo elettorale (nelle elezioni italiane del febbraio 2013) sia stato vanificato e le masse abbiano di nuovo anelato –ancora una volta– la propria repressione ? Siamo fermi nuovamente all’affermazione di Wilhelm Reich: sì, le masse hanno desiderato, in un determinato momento storico, il fascismo. Le masse non sono state ingannate, hanno capito molto bene il pericolo autoritario, ma l’hanno votato lo stesso. E il pensiero doppiamente preoccupante è il seguente: i due movimenti populisti autoritari, M5S e PdL, sommati insieme hanno più del 50% dell’elettorato italiano. Una situazione molto simile si è venuta a creare in UK, nel Maggio 2013, con il successo della formazione populista di destra dello UKIP. Le tossine dell’autoritarismo e del micro-fascismo perché e quanto sono presenti nella società europea contemporanea?

Parlare di 'micro-fascismo' per di più è utile nella misura in cui richiama la nostra attenzione alle pratiche sociali quotidiane e agli investimenti affettivi che rafforzano i centri di potere: il fascismo può svilupparsi, almeno in parte, per il desiderio o di un senso d'ordine o di partecipazione, per sentirsi parte di qualcosa, un desiderio che può diventare particolarmente forte in tempi di crisi e che può manifestarsi in modi autoritari. Questo è il motivo per cui dobbiamo essere particolarmente diffidenti nei confronti del 'populismo digitale' di una forza come il "grillismo": il suo appello al desiderio delle persone di sentirsi parte di un 'movimento' è rafforzato dal potere d'attrazione narcisistico dei social media.

Infine, una spiegazione approfondita dell'attuale ascesa degli autoritarismi richiederebbe un'analisi storica, concreta, di lungo periodo, che comprenda, non solo l'attuale crisi economica, ma anche una serie di altri fattori tra i quali va incluso - ma non limitato a - l'ascesa del neoliberismo negli ultimi trent’anni, l'aumento della disoccupazione, il depotenziamento e declino dei sindacati e della sinistra socialdemocratica.

- 1919, 1933, 2013. Sulla crisi

OC Slavoj Zizek ha affermato, già nel 2009, che quando il corso normale delle cose è traumaticamente interrotto, si apre nella società una competizione ideologica “discorsiva” esattamente come capitò nella Germania dei primi anni ’30 del Novecento quando Hitler indicò nella cospirazione ebraica e nella corruzione del sistema dei partiti i motivi della crisi della repubblica di Weimar. Zizek termina la riflessione affermando che ogni aspettativa della sinistra radicale di ottenere maggiori spazi di azione e quindi consenso risulterà fallace in quanto saranno vittoriose le formazioni populiste e razziste, come abbiamo poi potuto constatare in Grecia con Alba Dorata, in Ungheria con il Fidesz di Orban, in Francia con il Front National di Marine LePen e in Inghilterra con le recentissime vittorie di Ukip. In Italia abbiamo avuto imbarazzanti “misti” come la Lega Nord e ora il M5S, bizzarro rassemblement che pare combinare il Tempio del Popolo del Reverendo Jones e Syriza, “boyscoutismo rivoluzionario” e disciplinarismo delle società del controllo. Come si esce dalla crisi e con quali narrazioni discorsive “competitive e possibilmente vincenti”? Con le politiche neo-keynesiane tipiche del mondo anglosassone e della terza via socialdemocratica nord-europea o all’opposto con i neo populismi autoritari e razzisti ? Pare che tertium non datur.

SC L’analisi di Zizek è stata confermata: nel momento della sua più grande crisi, il capitalismo neoliberista è stato rafforzato piuttosto che indebolito. Le ragioni sono complesse, ma un elemento chiave è stata la sua vittoria nella “competizione ideologica”. Nel Regno Unito, ad esempio, la crisi economica è stata accusata di essere figlia delle politiche “dispendiose” del precedente governo laburista - da qui la necessità di ciò che viene eufemisticamente definita “austerità”. In realtà, questa “narrazione” è ormai così ampiamente accettata che l'attuale governo si è già spostato su una nuova storia che sottolinea la necessità di competere in una “gara” mondiale (e così deregolamentare gli affari, abbassare le tasse e i salari, togliere i diritti del lavoro, etc.). Abbiamo quindi bisogno di una narrazione alternativa. Ma spero che la nostra scelta non sia semplicemente tra autoritarismo neo-populista e neo-keynesismo! Anzi, questa mi sembra una falsa alternativa: se il populismo è quel movimento che pretende di unire una società, mentre in realtà oscura i reali rapporti di potere e le forme di lotta, allora si potrebbe sostenere che il keynesismo è di per sé una forma di populismo, in quanto propaganda la fantasia di un capitalismo di cui possono beneficiare tutti. Ciò non esclude tuttavia la possibilità che potremmo aver bisogno di una sorta di keynesismo strategico, a difesa dello stato sociale, dei diritti del lavoro, delle provvidenze del settore pubblico, etc.: dato il contesto attuale, difendere il welfare è un gesto radicale.

La sinistra deve tuttavia affrontare una serie di difficoltà nello sviluppare la propria narrazione. In primo luogo, esiste una concorrenza ideologica all’interno della sinistra stessa. La destra ha un compito più semplice: è più facile difendere lo status quo piuttosto che sfidarlo. In secondo luogo, qualsiasi analisi di sinistra si concentrerà su strutture apersonali, difficili da incorporare all’interno di narrazioni popolari (è il motivo per cui non ci sono molti buoni film o romanzi marxisti). Questa è una delle ragioni per cui, invece, otteniamo narrazioni populiste con protagonisti ben definiti ai quali attribuire ogni colpa (banchieri, immigrati, burocrati, etc.). Infine, vi è la difficoltà di diffondere narrazioni alternative nei canali di diffusione che sono per lo più di proprietà e gestiti proprio da coloro che stiamo cercando di sfidare. I social media qui potrebbero essere utili, ma non operano in un vuoto bensì all'interno dello stesso complesso di relazioni sociali dei media tradizionali e i suoi attori sono soggetti alle stesse pressioni ideologiche, alle stesse censure statali e aziendali e (come abbiamo visto di recente) allo spionaggio. Inoltre - come si è visto con il M5S in Italia - i social media si comportano spesso come una gigantesca cassa di risonanza della stupidità: non sono necessariamente favorevoli al pensiero critico.

La sinistra deve tuttavia affrontare una serie di difficoltà nello sviluppare la propria narrazione. In primo luogo, esiste una concorrenza ideologica all’interno della sinistra stessa. La destra ha un compito più semplice: è più facile difendere lo status quo piuttosto che sfidarlo. In secondo luogo, qualsiasi analisi di sinistra si concentrerà su strutture apersonali, difficili da incorporare all’interno di narrazioni popolari (è il motivo per cui non ci sono molti buoni film o romanzi marxisti). Questa è una delle ragioni per cui, invece, otteniamo narrazioni populiste con protagonisti ben definiti ai quali attribuire ogni colpa (banchieri, immigrati, burocrati, etc.). Infine, vi è la difficoltà di diffondere narrazioni alternative nei canali di diffusione che sono per lo più di proprietà e gestiti proprio da coloro che stiamo cercando di sfidare. I social media qui potrebbero essere utili, ma non operano in un vuoto bensì all'interno dello stesso complesso di relazioni sociali dei media tradizionali e i suoi attori sono soggetti alle stesse pressioni ideologiche, alle stesse censure statali e aziendali e (come abbiamo visto di recente) allo spionaggio. Inoltre - come si è visto con il M5S in Italia - i social media si comportano spesso come una gigantesca cassa di risonanza della stupidità: non sono necessariamente favorevoli al pensiero critico.

- Sul popolo che manca

OC Mario Tronti afferma che “c’è populismo perché non c’è popolo”. Tema eterno, quello del popolo, che Tronti declina in modalità tutte italiane in quanto “le grandi forze politiche erano saldamente poggiate su componenti popolari presenti nella storia sociale: il popolarismo cattolico, la tradizione socialista, la diversità comunista. Siccome c’era popolo, non c’era populismo.” Pure in ambiti di avanguardie artistiche storiche, Paul Klee si lamentava spesso che era “il popolo a mancare”. Ma la critica radicale al populismo - è sempre Tronti che riflette - ha portato a importanti risultati: il primo, in America, alla nascita dell’età matura della democrazia; il secondo, nell’impero zarista, la nascita della teoria e della pratica della rivoluzione in un paese afflitto dalle contraddizioni tipiche dello sviluppo del capitalismo in un paese arretrato (Lenin e il bolscevismo). Ma nell’analisi della situazione italiana ed europea è tranchant: “Nel populismo di oggi, non c’è il popolo e non c’è il principe. E’ necessario battere il populismo perché nasconde il rapporto di potere”. L’abilità del neo-populismo, attraverso l'utilizzo spregiudicato di apparati economici-mediatici-spettacolari-giudiziari, è nel costruire costantemente "macchine di popoli fidelizzati” più simili al “portafoglio-clienti” del mondo brandizzato dell’economia neo-liberale. Il "popolo" berlusconiano è da vent’anni che segue blindato le gesta del sultano di Arcore; il "popolo" grillino, in costruzione precipitosa, sta seguendo gli stessi processi identificativi totalizzanti del “popolus berlusconiano”, dando forma e topos alle pulsioni più deteriori e confuse degli strati sociali italiani. Con le fragilità istituzionali, le sovranità altalenanti, gli universali della sinistra in soffitta (classe, conflitto, solidarietà, uguaglianza) come si fa popolo oggi? E’ possibile reinventare un popolo anti-autoritario? E’ solo il popolo o la politica stessa a mancare?

- Sul Controllo

OC Gilles Deleuze nel Poscritto delle Società di Controllo, pubblicato nel maggio del 1990, afferma che, grazie alle illuminanti analisi di Michel Foucault, emerge una nuova diagnosi della società contemporanea occidentale. L’analisi deleuziana è la seguente: le società di controllo hanno sostituito le società disciplinari allo scollinare del XX secolo. Deleuze scrive che “il marketing è ora lo strumento del controllo sociale e forma la razza impudente dei nostri padroni”. Difficile dargli torto se valutiamo l’incontrovertibile fatto che, dietro a due avventure elettorali di strepitoso successo - Forza Italia e Movimento 5 Stelle - si stagliano due società di marketing: la Publitalia 80 di Marcello Dell’Utri e la Casaleggio Asssociati di Gianroberto Casaleggio. Meccanismi di controllo, eventi mediatici quali gli exit polls, sondaggi infiniti, banche dati in/penetrabili, data come commodities, spin-doctoring continuo, consensi in rete guidati da influencer, bot, social network opachi, digi-squadrismo, echo-chambering dominante, tracciabilità dei percorsi in rete tramite cookies: queste sono le determinazioni della società post-ideologica (post-democratica?) neoliberale. La miseria delle nuove tecniche di controllo rivaleggia solo con la miseria della “casa di vetro” della trasparenza grillina (il web-control, of course). Siamo nell’epoca della post-politica, afferma Jacques Ranciere: Come uscire dalla gabbia neo-liberale e liberarci dal consenso ideologico dei suoi prodotti elettorali? Quale sarà la riconfigurazione della politica - per un nuovo popolo liberato - dopo l’esaurimento dell’egemonia marxista nella sinistra?

SC Bella domanda! Purtroppo non ha una risposta semplice. La missione iniziale è semplicemente quella di aprire spazi in cui possa essere discussa questa stessa domanda. È per questo che, pur con tutti i suoi difetti e problemi, il movimento Occupy Wall Street è stato, per un breve periodo, promettente. E’ stato criticato per non aver saputo offrire una visione alternativa, ma questa critica non coglie il punto che l’alternativa di Occupy Wall Street era performativa: l'atto di occupazione era un’opzione alla sempre più brutale privatizzazione dello spazio, una rivendicazione di un ambiente in cui, tra l'altro, il dibattito potrebbe fisicamente aver luogo.

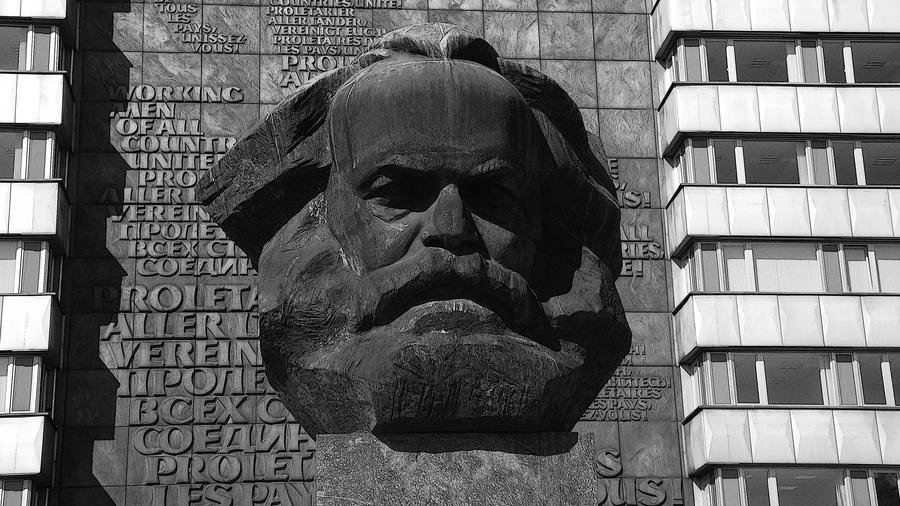

Il marxismo ha qui un ruolo importante da svolgere: la sua egemonia può essersi esaurita, nel senso che non domina più la politica di sinistra radicale in Europa - anche se nel Regno Unito è sempre stata marginale - ma fornisce ancora la più rigorosa e potente critica del capitalismo che dovrebbe essere il nostro vero obiettivo. E’ anche un modello da utilizzare per fare politica: come è noto, Marx - alla pari di Foucault - non ha passato il proprio tempo a creare progetti per il futuro bensì a sviluppare e affinare analisi del presente che, anche ai giorni nostri, potrebbero essere utilizzate da coloro che partecipano alle lotte esistenti, da cui poi le alternative concrete si sviluppano.

Sulla “Googlization” della politica; l’aspetto finanziario

del populismo digitale

Il marxismo ha qui un ruolo importante da svolgere: la sua egemonia può essersi esaurita, nel senso che non domina più la politica di sinistra radicale in Europa - anche se nel Regno Unito è sempre stata marginale - ma fornisce ancora la più rigorosa e potente critica del capitalismo che dovrebbe essere il nostro vero obiettivo. E’ anche un modello da utilizzare per fare politica: come è noto, Marx - alla pari di Foucault - non ha passato il proprio tempo a creare progetti per il futuro bensì a sviluppare e affinare analisi del presente che, anche ai giorni nostri, potrebbero essere utilizzate da coloro che partecipano alle lotte esistenti, da cui poi le alternative concrete si sviluppano.

Sulla “Googlization” della politica; l’aspetto finanziario

del populismo digitale

- OC La prima decade del XXI secolo è stata

caratterizzata dall'insorgenza del neo-capitalismo

definito "cognitive capitalism"; in questo contesto

un'azienda come Google si è affermata come la

perfetta sintesi del web-business in quanto non

retribuisce, se non in minima parte, i contenuti che

smista attraverso il proprio motore di ricerca. In

Italia, con il successo elettorale del M5S, si è

assistito, nella politica, ad una mutazione della

categoria del prosumer dei social network: si è

creata la nuova figura dell'elettore-prosumer, grazie

all'utilizzo del blog di Beppe Grillo da parte degli attivisti - che forniscono anche parte cospicua dei contenuti - come

strumento essenziale di informazione del

movimento. Questo www.bellegrillo.it è un blog/sito commerciale, alternativo alla tradizione free-copyright del creative commons; ha un numero

altissimo di contatti, costantemente incrementato

in questo ultimo anno. Questa militanza digitale

produce introiti poiché al suo interno vengono

venduti prodotti della linea Grillo (dvd, libri e altri

prodotti editoriali legati al business del

movimento). Tutto ciò porta al rischio di una

googlizzazione della politica ovvero ad un radicale

cambio delle forme di finanziamento grazie al

"plusvalore di rete", termine utilizzato dal

ricercatore Matteo Pasquinelli per definire quella

porzione di valore estratto dalle pratiche web dei

prosumer. Siamo quindi ad un cambio del

paradigma finanziario applicato alla politica?

Scompariranno i finanziamenti delle

lobbies, i finanziamenti pubblici ai partiti e al

loro posto si sostituiranno le micro-donazioni

via web in stile Obama? Continuerà e si rafforzerà lo sfruttamento dei

prosumer-elettori? Infine che tipo di rischi

comporterà la “googlization della politica”?

SC Il compito principale dello Stato, oggi, è di rappresentare il capitale. I politici tradizionali sono legati a questo compito: le micro-donazioni di Obama non hanno reso le sue politiche meno autoritarie o meno neo-liberali. Se esistesse una 'googlizzazione della politica’, allora io suggerirei che si riferisse a qualcos’altro e cioè al crescente potere politico dell'industria hi-tech: al suo ruolo sempre più potente come gruppo di pressione, allo sviluppo di giganteschi monopoli, al ruolo volontario delle techno-industrie all'interno della sorveglianza di Stato e così via. Google è una società come tutte le altre - e, in quanto tale, non esattamente a sostegno di finalità democratiche o emancipatorie.

Sul populismo digitale, sul capitalismo affettivo

OC James Ballard affermò che, dopo le religioni del

Libro, ci saremmo dovuti aspettare le religioni della

Rete. Alcuni affermano che, in realtà, una prima

techno-religione esiste già: si tratterebbe del

Capitalismo Affettivo. Il nucleo di questo culto

secolarizzato sarebbe un mix del tutto

contemporaneo di tecniche di manipolazione

affettiva, politiche del neo-liberalismo e pratiche

politiche 2.0. In Italia l'affermazione di M5S ha

portato alla ribalta il primo fenomeno di successo

del digi-populismo con annessa celebrazione del

culto del capo; negli USA, la campagna elettorale di

Obama ha visto il perfezionarsi di tecniche di

micro-targeting con offerte politiche personalizzate

via web. La nuova frontiera di ricerca medica e

ricerca economica sta costruendo una convergenza

inquietante tra saperi in elaborazione quali: teorie

del controllo, neuro-economia e neuro-marketing.

Foucault, nel gennaio 1976, all'interno dello schema

guerra-repressione, intitolò il proprio corso

"Bisogna difendere la società". Ora, di fronte alla

friabilità generale di tutti noi, come

possiamo difenderci dall'urto del capitalismo

affettivo e delle sue pratiche scientifico-

digitali ? Riusciremo ad opporre un sapere

differenziale che - come scrisse Foucault -

deve la sua forza solo alla durezza che

oppone a tutti i saperi che lo circondano?

Quali sono i pericoli maggiori che corriamo

riguardo ai fenomeni e ai saperi di

assoggettamento in versione network

culture?

SC Il mondo digitale introduce nuove aperture e possibilità offrendo alle persone potenziali modi per diventare politicamente attive ma purtroppo porta con sé anche alcuni rischi: il focus su velocità e simultaneità non aiuta necessariamente una riflessione critica profonda e la natura delle attività digitali, spesso individuali e private, non sono sicuramente favorevoli alle lotte collettive. Dobbiamo riflettere su questi problemi senza ricorrere a giudizi morali che semplicemente li celebrino o li condannino, resistendo sia alla propaganda tecno-utopista promossa dal settore tecnologico-industriale sia all'ansia reazionaria e nostalgica che gonfia la novità della tecnologia digitale catastrofizzando il suo impatto. Quello che ci serve, invece, è un’imparziale analisi storico-materialista che individui questi sviluppi all’interno del capitalismo contemporaneo, esaminando l'impatto delle nuove tecnologie sulla distribuzione di ricchezza e potere, e collocando gli utilizzi della tecnologia digitale entro i rapporti sociali esistenti.

E, ovviamente, dovremmo evitare di vedere le tecnologie digitali come una panacea. Mi ha sempre colpito una frase di Deleuze che mi sembra, ora, più pertinente: “Non è vero che soffriamo di incomunicabilità; viceversa soffriamo per tutte le forze che ci costringono ad esprimerci quando non abbiamo granchè da dire” (1). Questo è uno dei nostri compiti oggi: resistere alla richiesta di dover dire comunque qualcosa.

1) Gilles Deleuze: Pourparler (pg. 183) - Quodlibet, 2000

E, ovviamente, dovremmo evitare di vedere le tecnologie digitali come una panacea. Mi ha sempre colpito una frase di Deleuze che mi sembra, ora, più pertinente: “Non è vero che soffriamo di incomunicabilità; viceversa soffriamo per tutte le forze che ci costringono ad esprimerci quando non abbiamo granchè da dire” (1). Questo è uno dei nostri compiti oggi: resistere alla richiesta di dover dire comunque qualcosa.

Simon Choat, inglese, è Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations alla Kingston University, London (Uk) ed è l'autore del libro Marx Through Post-Structuralism: Lyotard, Derrida, Foucault, Deleuze (Continuum, Uk, 2010). L'area di ricerca che sta sviluppando include i Grundrisse di Marx, le filosofie neo-materialiste, le politiche demografiche e il fenomeno della disoccupazione, il marxismo di Alfred Sohn-Rethel. E' membro del Political Studies Association Marxism Specialist Group (PSA-MSG). E' in fase di stampa l'ultimo saggio 'From Marxism to poststructuralism' compreso nella raccolta di saggi curata da Dillet, Mackenzie e Porter (eds.) The Edinburgh companion to poststructuralism. (Edinburgh University Press, Uk, 2013). Attualmente sta scrivendo la Reader's Guide to Marx's Grundrisse per Bloomsbury Publishing di Londra.

—

Bibliografia

1) testi di riferimento alla domanda Sul micro-fascismo

Wu Ming, Yet another right-wing cult coming from Italy, via Wu Ming blog.

Wu Ming, Yet another right-wing cult coming from Italy, via Wu Ming blog.

Wilhelm Reich, Psicologia di massa del fascismo - Einaudi, 2002

Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Mille Piani, Castelvecchi, 2010

Gilles Deleuze, L’isola deserta e altri scritti, Einaudi, 2007 (cfr. pg. 269, 'Gli Intellettuali e il Potere', conversazione con Michel Foucault del 4 marzo 1972) “Questo sistema in cui viviamo non può sopportare nulla: di qui la sua radicale fragilità in ogni punto e nello stesso tempo la sua forza complessiva di repressione” (intervista a Deleuze e Foucault, pg. 264)

2) testi di riferimento alla domanda Sulla Crisi

Slavoj Zizek, First as Tragedy, then as Farce. Verso, Uk, 2009 (pg. 17)

Slavoj Zizek, First as Tragedy, then as Farce. Verso, Uk, 2009 (pg. 17)

3) testi di riferimento alla domanda Sul popolo che manca

Mario Tronti, 'C’è populismo perché non c’è popolo', in Democrazia e Diritto, n.3-4/2010.

Mario Tronti, 'C’è populismo perché non c’è popolo', in Democrazia e Diritto, n.3-4/2010.

Paul Klee, Diari 1898-1918. La vita, la pittura, l’amore: un maestro del Novecento si racconta - Net, 2004

Gilles Deleuze, Fèlix Guattari, Millepiani (in '1837. Sul Ritornello' pg. 412-413)

4) testi di riferimento alla domanda Sul controllo

Jacques Ranciere, Disagreement. Politics and Philosophy, UMP, Usa, 2004

Jacques Ranciere, Disagreement. Politics and Philosophy, UMP, Usa, 2004

Gilles Deleuze, Pourparler, Quodlibet, Ita, 2000 (pg. 234, 'Poscritto sulle società di controllo')

Saul Newman, 'Politics in the Age of Control', in Deleuze and New Technology, Mark Poster and David Savat, Edinburgh University Press, Uk, 2009, pp. 104-122.

5) testi di riferimento alla domanda Sulla googlizzazione della politica

Guy Debord, La società dello spettacolo, 1967 - II sezione - Merce come spettacolo, tesi 42,43,44 e seguenti fino alla 53.

Matteo Pasquinelli Google's Pagerank Algorithm, http://matteopasquinelli.com/docs/Pasquinelli_PageRank.pdf

Nicholas Carr, The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google (New York: W.W. Norton, 2008)

6) testi di riferimento alla domanda Sul populismo digitale e sul capitalismo affettivo

Tony D. Sampson, Virality, UMP, 2012

Michel Foucault, Security, Territory and Population, Palgrave and Macmillan, 2009

Michel Foucault, Society Must be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France 1975—76, Saint Martin Press, 2003

Dipinto: Stelios Faitakis