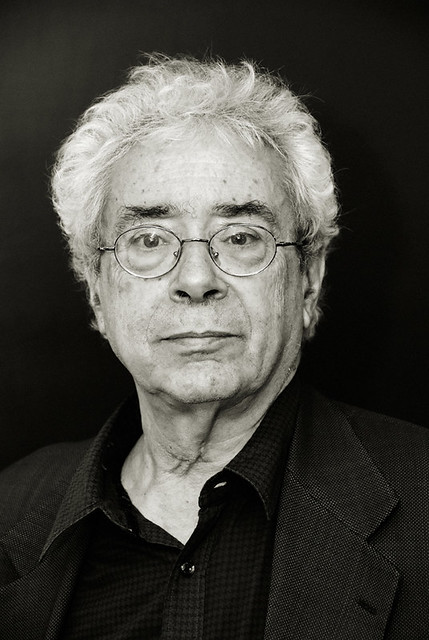

Books and Ideas: Luc Boltanski, you are a sociologist, a professor at the EHESS, [1] and you are well known for having directed and participated in numerous projects over several decades. This interview gives us an opportunity to reflect on two works that you recently published. First, Rendre la réalité inacceptable (Making Reality Unacceptable) is a short book in which you look back at the creation of Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales. The book was published on the occasion of the republication of an article that you co-wrote with Pierre Bourdieu, entitled “The Production of the Dominant Ideology.” The other book, On Critique, considers a series of tools and concepts for rethinking the connection between two clearly identifiable periods of your career. The first stage was that of critical sociology, in which you participated on Pierre Bourdieu’s team as one of his most industrious researchers. The next period was that of a sociology of critique, marked by the founding of the GSPM, [2] in which you reinvented a number of tools for understanding the place of critique in contemporary society. A first and very simple question is: what were you trying to do in these two books? Are you returning to critical sociology, or are you taking stock of your intellectual itinerary, which has gone through several stages? How do you interpret this gesture of republishing and returning to different epochs of your career?

The Critique of Critique

Luc Boltanski: There are several answers to your question. The first is to borrow a phrase from Albert Hirschman that I like very much (I like him, his work, and the phrase): “a tendency towards self-subversion.” I think that I have a pronounced tendency towards critique—towards critique in general, the critique of my friends, and self-critique or self-subversion. And I hate dogmatism. I think that nothing is as opposed to science and intellectual activity as dogmatism. The turn that we made in the mid-eighties, by creating a small group, which included people who had worked with Bourdieu, was an anti-dogmatic turn, not a political one. We were not trying to critique critique, though our actions were often interpreted that way. I think this is part of the reason for the hostility that our work elicited. Some took us to task, saying: “Ah, they’re abandoning critique, they are against critique, they’re turncoats, they’ve become free marketeers, and so on.” Others, to the contrary, said: “That’s great! They have shown that critique is finite, that we had arrived at a post-critical era, etc.” Those are almost exactly the words that were used. But both reactions were completely off the mark. Our problem was sociology. It was to fight against what was becoming, after the creativity of the seventies, a kind of dogmatism, a kind of intellectual routine. We wanted to reopen a number of theoretical problems in sociology that had, in my mind, yet to be resolved. It is important to shed light on problems, even when one does not manage to resolve them.

The status of the two books you mention is somewhat different. The first,Rendre la réalité inacceptable, is a book I wrote for young people—students, but also young people who are not students. I will perhaps return to this point. I wanted to convey to them what it means to work freely, to invent, to be ironic—I am a strong believer in irony—particularly in the years following May 68. I also wanted, at the same time, to republish “The Production of the Dominant Ideology.” First, I had a lot of fun being involved in the writing of that long article. I created a “Dictionary of Received Ideas” for the time, which was a rather enjoyable task. But it also struck me as useful to republish the article, both for historical reasons and to shed light on the political era in which we presently find ourselves. The texts that it analyzes—those of Giscard, Poniatowski, or of contemporary economists—lie at the frontier of two outlooks: between, on the one hand, what at the time was called “technocracy,” which was still deeply statist, still deeply tied to the idea of economic planning, rationality, and industrialization; and, on the other—I’m using big words to simplify things—neoliberal forms of governance. It is very illuminating to return to the middle of the seventies if one wants to undertake the archaeology of the Sarkozian political universe, which has considerably expanded neoliberal policies while dressing them up, at times, in so-called “republican” rhetoric. And, at a personal level, I wanted to clarify, perhaps because I’m getting older and I don’t want to bring a bunch of old, vain quarrels before Saint Peter, my relationship with Bourdieu, which was a very close one—asymmetrical, of course, because I was his student, but also a true friendship—one that, I think, went both ways.

On Critique is a little different. It is a theoretical book. It is the first time that I have written a theoretical book that is not tied to investigative work. It is, in a sense, the theory that underlies The New Era of Capitalism. I sought to build a framework that integrated elements connected to critical sociology and elements relating to the sociology of critique. You could say, if you like, that it is Popperian. Last weekend I was rereading some texts by Popper for a book that I’m currently writing. I am far from being Popperian at all levels, but I am in complete agreement with the idea that scientific work consists of establishing models that start from a particular point of view, even though one is fully aware that this point of view is local. The important thing is not to try to expand this local point of view by applying it to everything, which is one of the primary causes of dogmatism. But one can try to build broader frameworks, in which the previously established model remains valid, on the condition that the scope of its validity is specified. In a nutshell, what worried us most about Bourdieusian sociology as it had developed was the outlandish asymmetry between, on the one hand, the great, clairvoyant researcher and, on the other, actors who were steeped in illusion. The researcher was seen as enlightening the actor. Rancière made the same critique.

Combining Structuralism and Phenomenology

Books and Ideas: Yes, he does so in The Philosopher and His Poor, which you mention. There is this asymmetry and then—to leap directly into the debate between critical sociology and the sociology of critique—there is another issue that you discuss in On Critique. Basically, when one has a theory of domination that encompasses everything, one no longer sees domination in any particular place. When domination is everywhere, it is nowhere. Could you reflect on this gesture of discerning the spaces from which domination is practically exercised? The turn to a sociology of critique has been interpreted as an abandonment of the problematic of domination, whereas it seems, from reading On Critique, that something else is at stake.

Luc Boltanski: I think that it is closely tied to another problem that lies at the very heart of sociology and that deeply preoccupied Bourdieu—which he tried to resolve without, in my view, really succeeding. It is a problem that, moreover, has yet to find a genuinely satisfying solution. It goes more or less like this. You can approach social reality from two perspectives. You can take the point of view of someone newly arrived in this world, to whom you will describe this reality. This requires a panoramic point of view, a historical narrative, reference to large entities and collectivities, which may or may not have juridical definitions: states, social classes, organizations, etc. Some will speak of references to structures. A perspective of this kind will tend to shed light on the stability of social reality, on the perpetuation of its asymmetries (to use Bourdieu’s language), on reproduction, and on the great difficulties actors encounter in altering their social destiny or—more difficult still—in transforming structures. But you can also adopt another perspective, which is called the sociology of the actor, that consists of adopting the point of view of someone who acts in the world, who is immersed in situations. No one acts within structures, we all act in determinant situations. And there, you no longer find yourself confronted with actors who, as it were, passively endure reality, but with creative individuals, who calculate, have intuitions, deceive, are sincere, have competencies, and act in ways that modify their immediate reality. No one, in my mind, has found a really convincing solution to combining these two approaches. Yet they are both necessary in making sense of social reality.

One could try to formulate this problem in terms of the relationship between structuralism and phenomenology. I tried to articulate these two approaches inLa condition fœtale, starting with the question of breeding and abortion. I am not sure that it was particularly satisfying. Bourdieu tried to combine these two approaches. Before discovering the social sciences, he wanted to devote himself to phenomenology. For him, this articulation depends on the theory of the habitus, towards which I have a number of theoretical reservations. It is a theory that is derived, in large part, from cultural anthropology, as it was developed by anthropologists like Ruth Benedict, Ralf Linton, and Margaret Mead. I recently reread Patterns of Culture by Ruth Benedict, and it is quite strange to see, from a contemporary perspective, how she uses categories drawn from Nietzsche or Spengler. Her main idea is that one can identify cultures that have specific traits—personalities, if you will—and that these personalities will reappear in the psychological dispositions—i.e., in the personalities—of the individuals who are immersed in these cultures. It is a rather bizarre construction, one that becomes circular, so that if you know an actor’s cultural location, as defined by sociology and statistics, you know her dispositions and you know, in advance, how this actor will react in any given situation. It is against this position that we took a stand. But we also wanted to avoid a different model, established in opposition to the cultural model, which, without the help of phenomenology but drawing on neoclassical economics, acknowledges only individuals. According to the Popperian model, known today as methodological individualism, only individuals exist. Each individual has her own motives and makes her own choices, and it is from the aggregation of these various motives (which occurs in ways that are not explained) that historical causality is derived, be it a micro-history of situations or economic or political macro-history. In this model, which sees only individuals, it is forbidden to confer intentionality onto entities that are not individual beings. On the face of it, this seems reasonable. Social groups—political groups or social classes, for instance—cannot be the subjects of action verbs. But, in my view, one problem with this model is that it cannot account for the fact that it is not only sociologists who refer to macro-sociological entities. Everyone does. Actors cannot construct social reality without inventing institutions and collective entities, which they know, at a certain level, are fictions, but which they nonetheless require to make sense of what is happening—that is, history.

Our way of approaching the question of action has taken a hyper-empirical turn. We took our inspiration from currents in Anglo-Saxon pragmatism. In our work with Bourdieu, these currents were far from unknown. We had, for example, read Austin, and many authors tied to analytic philosophy. We were very familiar with interactionism and Goffman’s work. It was, incidentally, Bourdieu who first had Goffman translated and introduced him in France. But compared to what occurred in Bourdieu’s group, we radicalized this approach. Our intention was to develop an empirical sociology of critique. To this end, we chose disputes as our principal object of study, as it is through disputes that actors display their critical capacities. We wanted to do fieldwork on disputes that was as precise as possible, approaching them from a position of uncertainty. In other words, we considered—and in this we were very influenced by what Bruno Latour and the anthropology of sciences were doing at the time—all the arguments made in the course of a dispute, in a symmetrical way. For the new anthropology of science, one must not, for example, study the Pasteurian crisis by assuming that Pasteur was right and his adversaries were wrong, but to proceed as if one was faced with two competing theories that had to be treated equally in terms of description, rather than assuming, retrospectively, the position of the theory that won. We adopted the same approach when considering disputes in our fieldwork. We considered major controversies or minor disputes occurring in offices or companies, closely examining the critical capacities of the actors, with the goal of reconstructing a critical theory, somewhat like Dewey, on the basis of the critical experiences of the actors themselves.

The Making and Unmaking of Social Classes

Books and Ideas: We’ll return to the question of uncertainty, which lies at the heart of On Critique, as your thinking on institutions is connected to the notion of uncertainty. First, in order to understand what is at stake in the historical trajectory marked by the different stages of your thought, there is one social structure which you mention that plays a distinct role in both books: social class. In essence, a major part of your thinking about historical change in recent decades has consisted of saying: we are witnessing a decline, a quasi-disappearance, of entities that, thirty years ago, were considered almost natural. This has political consequences, both in terms of how ideology is formed and in terms of how sociology itself is formed. You say in On Critique that the turn to a sociology of critique and the return—I am not sure if “return” is the best word—the search for a rearticulation, is entirely connected to the presence or absence of social classes in our social world. Are we simply left with the assessment that social classes have nearly disappeared as structuring entities that are worked into the state apparatus, or do you see a revival of forms that actors might latch onto to escape their confining individualism?

Luc Boltanski: I would just like to point out one thing: the logic of scholarly research is not the same as the logic of politics. In the mid-eighties, it was less that we thought that social classes were no longer relevant than that we concluded they were no longer interesting fields of research. When authors have dealt with an issue thoroughly—you find the same thing with novels—you have to move onto another topic. To take a completely different example, after Bataille, it was no longer very interesting to write erotic literature, as he went as far as one could go. You have to move onto other topics. Well, it’s the same for research. I felt, particularly after the publication of Bourdieu’s Distinction, that an analysis of social classes relying on the concept of habitus was not a terrain on which my generation would make new discoveries, on which it might innovate. I remember that the English translator of The Making of a Class [3] told me that he found it difficult to translate “habitus.” I told him: no problem, pal, there’s no “habitus” in The Making of a Class. It was important to adopt different approaches, to interest oneself in other things. The Making of a Class is indeed a book on the formation of social classes, but which approaches them through their political genesis. I should add that this turn occurred at the historical moment when the socialists had come to power, after Mitterrand’s election. Basically, we thought, very naively, that certain things could now be taken for granted politically and that, by the same token, we were freed from the tiresome task of having to repeat incessantly that capitalists exist, that inequalities exist, that domination exists, etc. For the left, it was a rather optimistic period, even if, after the fact, one might think that we were mistaken.

To return to social classes, it is, as you know, an extremely complicated concept, because on the one hand it is a critical concept, oriented to the normative horizon of the disappearance of classes. Considered from this perspective, the description of exploited or dominated social classes is primarily negative. On the other hand, it is a positive concept that seeks to arm you for struggle, because if you describe people only in a negative way, you can’t arm them for struggle. This was a common practice of the Communist Party. You must show how poor, miserable, and oppressed the proletariat is. But you must also show that it is courageous and resistant and that it has its own values which underpin its dignity. Also, something happened in France in particular that did not occur in Great Britain to the same extent, nor in the United States.

After the Popular Front, in 1936, and after the establishment of the welfare state, in the postwar years, a political system was set up that tried to integrate social classes into the representation of the political order, to make them official, and to give them a role in the construction of the political collectivity. Until then, in France, the collectivity had been conceived in what we might call Rousseauist terms, that is, as composed of “pure” citizens, defined with no reference to their proprieties or interests, as “men without qualities,” if you like. This occurred somewhat along the lines of corporatism, while preserving the critical aspect of social classes, as well as, in part, their antagonistic character. By the same token, references to social classes became complex. It was simultaneously a critical notion and a concept used to describe the institutions of the welfare state. Social classes were also integrated into actors’ mental categories. In the early eighties, Laurent Thévenot and I wrote a study (that appeared in English) entitled “Finding One’s Way in Social Space.” [4] Our approach was through exercises that were almost games, carried out in groups. We showed how the socio-professional categories of the INSEE, [5] which were invented in 1936 following the establishment of the welfare state, had equivalents in the actors’ own cognitive categories. They were tools for defining one’s own identity and for identifying others. If you look at films from the seventies, like those of Claude Sautet, you see that in a way they are “Bourdieu Light”: you have specific milieus, people who have a specific personality because they belong to these milieus or to a social class, etc.

What happened in sociology in the eighties was that people said: these things have been established, we’re going to think about something else. It’s not that they’re wrong, but we’re going to go a step further, to understand how people construct these categories, how they have other ones, particularly by considering the phenomena of disadjustment that was starting to destroy the coherence of social classes as they had been established institutionally through the relationship between market and work, the system of classification, the world of schools, INSEE classifications by way of collective bargaining agreements, etc.

But, that said, the profound changes shaping the social world have been neglected. There has been another phenomenon, tied to changes in capitalism and in politics: the dismantling both of the critical force implicit in the notion of social class and of its institutional character as a tool for grasping the political world. To put things in slightly complicated terms, what I studied in The Making of a Class, without realizing it, was the establishment in the fifties of a very rigid boundary between, on the one hand, the labor movement and the world of labor, and, on the other hand, everything else. This is when the boundary hardened. Everyone else became known as cadres—managers—a word that lumped together workers who had become self-educated foremen and great industrialists trained at elite schools who had become corporate employees and which managed to make a reality out of this assemblage composed of people who belonged to the same entity but were incapable of describing this entity, in which no one had the same habitus. And this was, at the time, politically and economically necessary. Later, I would say, in the eighties and even more after 1989, following the collapse of communism and the threat that socialist countries posed during the Cold War, this boundary disintegrated. During my lifetime, I have witnessed the rise of the category of “manager,” as well as its fall. This category no longer seems at all necessary. “Worker” has been replaced by “operator.” Today, there are operators and “executives” or “project managers.” As I see it, one of the major trends now underway is the implementation of a divide that is not instituted and that is a divide separating “executives”—in a nutshell, the rich, society’s upper crust—from everyone else. The reason is that one no longer has to contain the working class, which has lost, which is no longer seen as a threat, and which has, in a sense, unraveled.

Books and Ideas: There is no longer a critical force that might be integrated into a discourse.

Luc Boltanski: No. Perhaps one will come back. But you could say that, in the thirties, everyone believed in social class: social Catholics, corporatists, those who would become fascists, socialists, communists, etc. Except for liberals, everyone believed that something like social classes existed and that it was necessary to consider them and integrate them into the state. And everyone believed very strongly in the state. This was the problematic that dominated the period extending from the thirties to as late as 1970. The period that immediately followed May 68 was really the apogee of the welfare state—before Giscard, who after all was a great politician (I have a lot of admiration for Giscard, even if I naturally disagree with most of his policies), endeavored to displace the social question and to entertain the possibility of a weakening of the unions, followed by a halt to, even a dismantling of, the welfare state.

Books and Ideas: Notably by promoting—you show that this is the flip-side of the decline of class—the collectivization of questions of gender and the societal questions that took their place.

Luc Boltanski: Absolutely. And he was right to do so against the moralizing opposition of the Gaullists. With regards to social class, we have thus arrived, in sociology, at a rather bizarre situation, which, in some respects, creates a convergence between the substantialist position of Bourdieu and that of someone like Rosanvallon, when he tried to explain that classes don’t or no longer exist. When I was writing The Making of a Class, Bourdieu, who nonetheless, I think, had considerable respect for this work, would tell me that, when you get down to it, managers don’t exist, at least not as a class, since, because of its heterogeneity, the category included actors endowed with different habiti. Then, several years later, Ronsavallon referring to our research on social categories—my work, as well as that of Desrosières and Thévenot, for example—wrote that these works showed that social classes don’t exist, that they were, in a sense, artifacts. This was a misunderstanding of our work. We were trying to define what you might call an ontology of collective beings. We wanted to investigate the modalities of existence of these “inexistent beings” (as logicians call them) that are collective entities. They do not exist as individual, substantive beings do, but they exist devilishly—if I might say so—albeit in other modalities of existence. Substantialism, which, in the seventies, was often invoked to defend the existence of classes, was later used to argue for their non-existence. So a new “taken-for-grantedness” was established in the eighties and nineties. Its basic insight was the idea that we no longer live in a class society. We live in a society with a broad middle class and a little fraction of the excluded who, out of charity, must be helped, and a little fraction on the top, composed of the rich, the too rich, who should be more mindful of the public good, of “living together,” etc.—in short, more moral, and whom we must try to make moral. This was the beginning of this moral society to which we still belong. I called our group the “Political and Moral Sociology Group” as an homage to Hirschman, but, personally, I don’t like moralism.

First published in www.laviedesidees.fr. Translated from French by Michaël C. Behrent with the support of the Institut Français.